Reformed theologian Dr. James White was recently attacked on Twitter over some comments he made about government overreach during the COVID-19 crisis. I don’t care to cover all the details, but it’s notable that even White’s soteriological nemesis opponent Dr. Leighton Flowers is sticking up for him. And as much as I’ve criticized White on this blog, I happen to think his tweets over the past couple weeks have been absolutely spot on regarding the erasure of our Constitutional liberties.

But I also think that White himself sometimes uses the very weapon (in a theological context) against his opponents that tyrannical governments use (in a social/political context) to manipulate and browbeat the people. That weapon is, of course, the degradation of attachment to specific tradition.

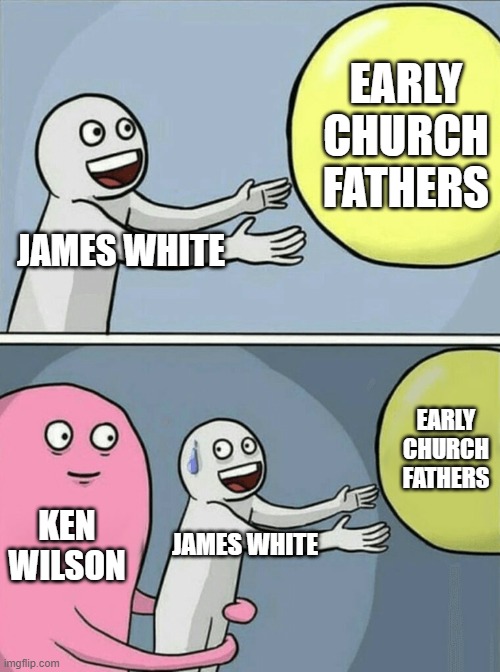

White frequently disparages tradition when engaged in theological debate. His open letter to Dave Hunt is a prime example, but White has also accused Dr. Flowers and other non-Calvinists of being blinded by or slavishly devoted to a theological tradition rather than Scriptural exegesis. The implied argument is that tradition is worthless when compared to a careful, rational exegesis of Scripture, so we should be quick to abandon our traditions.

The relevant political parallel is that significant government overreach requires convincing the people that advocating for existing (i.e., Constitutional) restraints on power is just a blind or slavish devotion to tradition. The implied argument is that political traditions are worthless in addressing this or that crisis, and that only a careful, rational (or “scientific”) approach to the problem will do, so we should be quick to abandon our traditions.

White would have us Americans remain firmly committed to our our legal traditions while trying to convince the vast majority of Christians worldwide (i.e., non-Calvinists) to reject their theological traditions. Is this position tenable? White’s certainly not guilty of a contradiction that I can see, but there is undoubtedly something fishy about treating tradition – abstractly considered – so very differently from one realm of human experience to the next.

White’s see-saw attitude toward traditions likely comes from simply never considering what the proper human attitude toward traditions ought to be. (I hasten to add this isn’t a criticism so much as a mere observation, since White isn’t a philosopher.) And while I won’t try to answer that question in a single blog post, perhaps I can sketch how someone with White’s commitments might modify his views to bring his political and theological approach to tradition closer together.

I propose that Protestants who regard Scripture as the only source of doctrinal authority ought to seriously reconsider Sola Scriptura. Instead, we ought to regard Scripture as first in theological matters in the same way that we ought to regard the U.S. Constitution as first in (U.S.) political matters.

What would this entail? Primarily, it would affirm the importance of exegesis; we need to understand the original meaning and intent of Scripture to engage in theology, just as we need to scrutinize the original meaning and intent of the Constitution to engage in statesmanship.

But here’s the kicker: Just as any serious constitutional lawyer must have a healthy understanding of (and some measure of deference to) the existing body of constitutional law, so the serious theologian must have a healthy understanding of (and some measure of deference to) Church tradition.

Notice that “some measure of deference to” doesn’t mean “absolute surrender to”, nor does it mean “place on equal footing with” the respective text. I think Protestants are right to be willing to question theological developments that are handed down and practiced in light of Scripture, just as we had better be willing to question political developments (e.g., Roe v. Wade) handed down and practiced in light of the Constitution itself.

If I thought tradition was equal to Scripture, I’d be a Roman Catholic. And if I thought constitutional law was equal to the Constitution, I’d be a pro-abortion, America-should-invade-the-world, eminent-domain-for-private-profit raging statist. I’m neither, because I recognize that traditions can and do go awry; it is therefore the proper role of reason to systematize and correct our traditions. (However, I am convinced that 2 Thess. 2:15 gives the Catholics a far stronger position – relatively speaking – than anything to which American progressive liberals might appeal in the Constitution.)

But to use reason to systematize and correct tradition, we must live and breathe within that tradition. It must be criticism from the inside, as one who loves and cherishes what his forefathers have handed down – even though it is imperfect.

I regard legalized abortion as an abomination; no doubt there are Protestants who feel much the same about purgatory or Papal infallibility. But in both cases, the choice is not between accepting what is handed down and secession/schism. Dissenting voices can work within a tradition to change its trajectory, while still maintaining unity in a larger sense. However, this third way is absolutely closed off so long as (1) Protestants are unwilling to accept tradition as a valid source of authority and (2) Catholics are unwilling to more critically examine certain traditions and practices.

Total disregard (or outright hatred) for tradition stands in the way of this larger unity. This is how progressive leftists have created such a serious rift in the American political fabric. The same arguably happened to Western Christianity in the Reformation (see Frank van Dun’s excellent paper here). In either case, I think healing and reconciliation – if it is to happen at all – can begin when tradition is restored to it’s proper place.

So let us applaud Dr. James White’s devotion to his American political tradition – imperfect as it is – and pray that he discovers why so many Christians are equally devoted to their imperfect theological traditions, too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.